Written by: Dunia Jørgensen, Edited by: Xenia Weulersse

If you imagine a worldwide sustainable transition, do you imagine empowering other countries to gain economic power and become self-sufficient at their own terms, or is the narrative of technology empowerment through charity and development work emerging foremost? Or maybe ‘underdeveloped’ countries will remain the testing ground for developed locked-in countries? When outsourced industries enter grounds of low governance and unstable regimes, the risk of undermining the norms of the context are high. Here is where damage occurs, regardless of intentions and the efficiency of the technology. By taking a closer look into water problematization areas, we can see the contradicting effects of industries and governments from a sustainable transition perspective.

In a collectively imagined sustainable future, distributed responsibility is not only a challenge for governments to align with, break down into actionable goals, but also the recognition that the vantage point of departure on a global scale is challenged by resource and economic disparities. Due to the homogeneity requirements for collective imagined futures, among others, Escobar criticises the field of Sustainable Design as being focused on reducing ‘unsustainability’. A globalized universality paradigm needs adjustment towards pluriverse perspectives, he states: the goal being coexistence of many worlds in the same place (Escobar, 2011). If diversity and multitudes are to exist, how can we fairly distribute responsibility across unequal nations, whose ecosystems are shared?

One can argue in such case, that water availability depends on the geological aspects of a region, predisposed by nature in areas of resource abundance, while others are naturally scarce e.g. desserts. But in these days, resource management are also directed through political decisions. Think about refugee camps, emergency areas and military bases. Where resources are needed, these can be allocated and provided.

Human technological advancements have further opened up the portal of possibilities rather than limitations by nature. It is no longer excusable to withhold the premises of resource limits in certain regards, with the exception of harmful substances for the environment, such as coal-based resources. But certainly not when it comes to resources deemed by the United Nations as Human Rights and included as one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s).

Water – the essential element of dignified life

The sixth goal, states: “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” (United Nations, 2015). It is transparently clear to all humans capable of reading this sentence, that water is another one of those matters of concern to us, at all levels. Individuals to planetary ecosystems.

Earlier even, The General Assembly at the United Nations recognized water accessibility and sanitation as a basic Human Right, stating that access to water should be affordable and physically accessible to all (United Nations, 2010).

Our dependency to water is undeniably long and integrated to our planet’s fundamental eco-biological systems’ homeostasis. Regardless of where you are born, whether framed as developed or underdeveloped, the need for water is indifferent on who’s lips it lands on with it’s crumbling thirst.

In Denmark however, groundwater reservoirs hold the status of abundant, as the water quality is drinkable when abstracted, requires little filtering for it’s consumption (although emerging pollutants are increasingly proposing a challenge to this statement through pesticide, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals and micro-plastics concentrations) and no additives (such as chloride) need to be added for it’s usability. We are geologically blessed, technologically capable and somewhat politically engaged to tackle these issues – also increasingly aware and proactive regarding flooding events due to climate change in the future.

What is our role then, in the larger global picture? If we can individually and politically-broadly agree that water requires international cooperation for it’s access and fair distribution, what is then left to do?

The role of transnational industries & the innovative west

In the same report mentioned earlier by The United Nations (2010), the following fact-box is to be found:

“About 90 per cent of sewage and 70 per cent of industrial waste in developing countries are discharged into watercourses without treatment, often polluting the usable water supply”

United Nations, 2010 ,pg. 9

Looking at the largest transnational companies for water supply and treatment technologies such as Veolia, SUEZ, SNF, Pentair, Parker-Hannifin, one can trace their Although today’s products are composed of various elements produced across nations, and also end up being used in various places, the credit is simplified to singular overarching manufacturers. Looking at the largest transnational companies for water supply and treatment technologies such as Veolia, SUEZ, SNF, Pentair, Parker-Hannifin, one can trace their origins to USA and France. Leading technological solutions stem therefore mostly from the western industrialized societies and are largely attributed to their development. This means that we also actively contribute to their further development by aiming to acquire clean water elsewhere.

Simultaneously, leading industries responsible for environmental water pollution and resource use are also attributed from the western industrial hemisphere. A study by Zhou and Li from Michigan University, points out: “a significant number of U.S. firms reduce their pollution at home by offshoring production to poor and less regulated countries.” (Zhou and Li, 2017). Loorbach points out, the co-evolving of collaborative networks and governance affects the societal structures and shapes the governance structure of a regime. Policy-making in that regard “becomes less transparent; the division of power, as well as the accountability issue, is no longer clear[…]” (Loorbach, 2010) In such cases, who is to be held accountable and how?

Carlsberg Group, a worldwide brewer with headquarters and roots in Copenhagen, published among others, a ZERO Water waste initiative aimed to reduce the water usage in brewery operations. This initiative is framed by their report to be ambitious and aims at reaching a reduction of water usage down to 50% by 2030 (Carlsberg Group, 2019)

In 2018, a Carlsberg brewery in Nepal was found to be the source of pollution in the third largest river (Narayani-river) and its nearby natural areas (Pedersen, 2018). Upon questioning, Carlsberg firstly denied being responsible for the severe pollution which was damaging the biodiversity of the area. It is not the first time Carlsberg breweries have being found by external auditors (like Danwatch) to have polluted regions around the world, as incidents in China, Laos and Malawi were reported years earlier.

Cheers! Technology fix for an eco-efficient future

Water treatment projects are complex orchestrations of socio-technical kind which can turn out damaging, much more than sustainable if left out in the positivist paradigm that proliferated along development work in the ‘global South’. In other words; myopic, if these are treated as merely discrete technical projects separated from their role and effect in shaping the context’s socio-political dimensions (Jensen et al, 2015). Areas in which infrastructure and law-enforcement (including fundamental environmental legislation) is lagging, proves as good grounds for experiments. Smith reminds us that the stability of a regime is a parameter of high influence towards niche adoption: when niche stability is high and regime stability low, opportunities for niche influence reach their highest (Smith, 2007). Therefore, in so-called underdeveloped areas, innovation fertility can be favorable, the question is still for whom and how do these affect their context? If a strong niche approaches an unstable regime, does a crisis-led-regime shut doors or let’s anyone in for heroic actions?

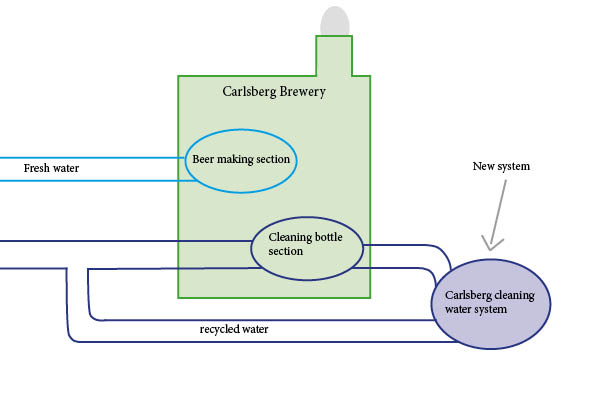

The newest green technology emerging from a triple-helix private collaboration with Danish stakeholders -within technology, water governance and industry- found a financially viable way to reuse water within a circular closed-system. This system has been successfully piloted and found investments at the Carlsberg Fredericia brewery in Denmark. Millions of Danish Kroner (DK currency) are now set aside to scale the technology in other breweries around the world.

For Carlsberg, it can be a winning situation to both be able to brand and qualify themselves as a sustainable enterprise at home-base aswell as a eco-efficient expert industry towards the local governments which provide permits to install breweries. It also could potentially lessen cases of pollutants such as the one in Nepal.

For environmental sustainability overall and financial viability executed through this technology, these are good news. Is the problem fixed then, when it comes to sustainable transitions for developing countries dealing with water resource scarcity? If Carlsberg truly aims to establish a long-term sustainable strategy, it is not enough to focus on energy or water efficiency. The land covered by their breweries will still be land taken.

#1 Design strategy: Investigate Practices and power effects

Practice Theory, a field which aims at understanding practice as an entity constructed of materials, objects, symbolism, competences, skills, etc. also takes into account power and governance. Watson (2017) explains:

In accounting for both social change and the reproduction of social stability as the result of human action, practice theory is inherently about power, if power is seen as capacity to act with effect.

Watson, 2017

If power is an effect, the practices embedded unveil the allowances and constraint of a system and individuals within. Practices can furthermore reveal the norms implicit in a defined context and broadly. It is therefore important to recognize how practices are related in across varying sites, and to what extend the local norms are supported by the suggested practices. When it comes to the Carlsberg, to understand the cultural norms in the intended places of installment, should be an important factor to consider. How does the local context perceive water? What are the practices attached to water processing and brewing? Adding the perspective of power as an effect, it is also foremost good to deconstruct the normalities surrounding the technological innovation. This practice inspection can be done at the Fredericia brewery. Once this is done a critical look at which normalities are context dependent and non-transferable to their intended context is essential.

#2 Design Strategy: Develop or adapt technologies in the context

In a Strategic Niche and Transition management perspective towards social innovation and adoption of systems innovation, the plasticity of so-called underdeveloped areas provides grounds for sustainability to co-emerge, as Ceschin undelines:

“If we want to effectively tackle sustainability, there is a need to move from a focus on product and production improvements only, towards a wider approach focused on producing structural changes in the way production and consumption systems are organized. In other words we need radical innovations.”

Ceschin, 2014, 1

If Carlsberg, Lifestraw and other technology stakeholders would invest time in applying co-designing practices as part of the development strategy the chances are that the products emerging will have a chance to stabilize in the regime. This also enables the creation and recognition of local value, empowering societies at multiple levels. As Ceschin suggests, the establishment of Living Labs, enable not only the technological niche to adapt, but also it does so under protected environment from a rigid regime. The benefits to knowledge enabling, exchange and participation should not be isolated to the engineers in Carlsberg. This puts the transition to continuously only bring few along sustainable prosperity long-term.

A true source of pride in our mirror image

A sustainable transition within life-essential resources should not only entail, finding ways to which radical innovations can survive and affect the current regimes and status-quo. It should also face the limitation of resources and stir the waters of the fundamental inequality reinforcing structures large transnationals thrive upon. If we all are responsible to the extend of our knowledge and actions, shouldn’t we also be held accountable for them? The answer is yes, as much as we take credit for development, we also need to take accountability for the harm done, also when it is outside our local boundaries.

We should recognize that the power dynamics along all, need attention to transition too. The sacrifice for our westernized enterprises lies also on letting others gain empowerment, influence the course of innovation and lead the adaptation of new technological species, such as the one by piloted Carlsberg. We might not be nr. 1 within innovative water technology, but we can exemplify how a sustainable technological transition can be realized, also for long-term benefits of those who need it.

REFERENCES

Carlsberg Group (2019) Sustainability Report 2019 [online] Available at: https://www.carlsberggroup.com/media/35965/carlsberg-as-sustainability-report-2019.pdf [Accessed 18/03/20]

Ceschin, F. (2014) How the Design of Socio-Technical Experiments Can Enable Radical Changes for Sustainability,International Journal of Design, Vol. 8 (3), pg. 1-21

Escobar, A. (2011) Sustainability: Design for the pluriverse, Society for international Development, 52(2), pg. 137-140

Hajjah, A. (2020)Hand-washing: a luxury millions of Yemenis can’t afford, France 24, AFP, Yemen [online] Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/20200324-hand-washing-a-luxury-millions-of-yemenis-can-t-afford [Accessed 26/03/20]

Jensen, J. S., Lauritsen, E. H, Fratini, C.F. Hoffmann, B. (2015) The harbour baths and the urban transition of water in Copenhagen: Junctions, navigation, and transition mediators, Environment and Planning A, 47(3) 554 – 570

Millan, A. (2015) Danes deliver clean water to 200,000 in Kenya, The Local DK [online] Available at: https://www.thelocal.dk/20151102/danish-projects-biggest-private-donation-in-africa [Accessed 26/03/20]

Pedersen, C. B. (2018) Knuste flasker og forurening belaster Carlsberg bryggeri i Nepal[online] Available at: https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/penge/knuste-flasker-og-forurening-belaster-carlsbergs-bryggeri-i-nepal [Accessed 18/03/20]

Smith, A. (2007) Translating Sustainabilities between Green Niches and Socio- Technical Regimes,Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 19:4, pg. 427 – 450

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, General Assembly, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015

United Nations (2010) The Right To Water: Fact sheet nr. 35,, Office of the UnitedNations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Switzerland,Geneva [online] Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet35en.pdf [Accessed 18/03/20]

Zhou, Y.M. and Li, X. (2017) Offshoring Pollution while Offshoring Production?, Strategic Management, Vol 38, 11, November 2017, pg. 2310-2329